Ever felt stuck in your fitness routine? A deload week might just be the breakthrough you need. Dive into this guide and learn how taking a step back can propel you forward, why your body craves it, and the right way to do it for maximum results.

Jump to:

- What is a Deload Week?

- How Deloads Work

- Signs that You Need a Deload Week

- How to Program a Deload Week

- Types of Deloads

- Benefits of Deloads

- Who Should Schedule a Deload Week

- Sample Deload Week

- The Science Behind Deloading

- What Should You Do After Your Deload?

- Frequently Asked Questions

- How often should a deload week be implemented?

- What are the benefits of a deload week in powerlifting?

- What percentage of weight should be used during a deload week?

- How does a deload week affect bodybuilding training?

- What is the role of cardio during a deload week?

- When is the best time to schedule a deload week in a training program?

What is a Deload Week?

It’s a planned period of reduced training intensity and volume, aimed at enhancing your recovery and preventing overtraining. Typically scheduled every four to eight weeks, it can help you optimize your gains and maintain long-term progress in the gym.

You can typically alter one or more of three training variables: load, volume, and intensity. For example, you might reduce the weight you’re lifting, decrease the number of sets or reps, or lower the overall intensity of your workouts.

The purpose is to give your body and mind some rest, allowing you to return to your regular training regimen with renewed energy and focus.

How Deloads Work

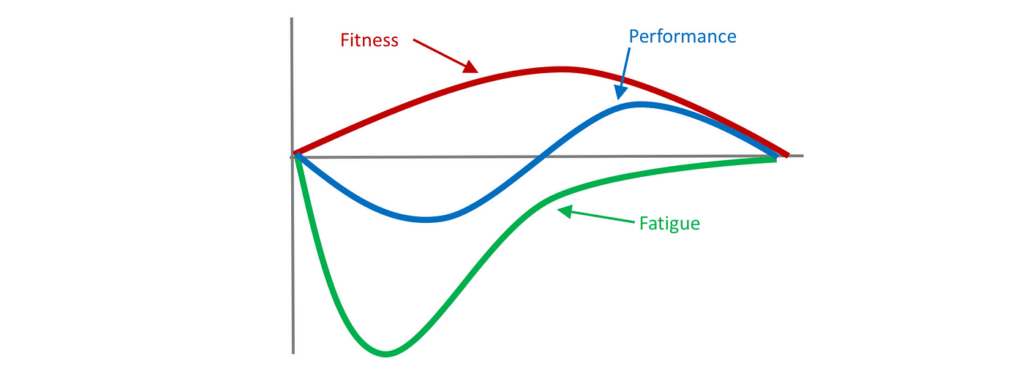

Fitness-Fatigue Model

The Fitness-Fatigue Model suggests that training leads to both fitness gains and fatigue. While the fitness gains help improve your performance, the accumulated fatigue can hinder it. The idea is to reduce your training intensity or volume, allowing your body to recover from fatigue. As a result, you’ll notice improved performance and reduced risk of injury.

General Adaptation Syndrome

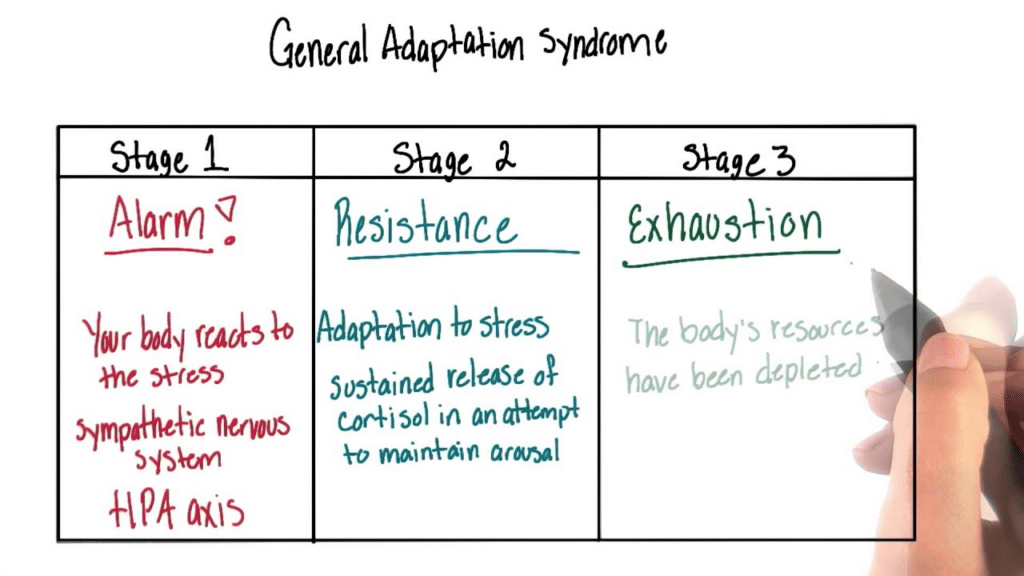

The General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) is another concept that helps explain deload weeks. GAS suggests that the body goes through three stages in response to stress:

- Alarm Stage: Your body experiences an initial shock due to the increased stress from training. You will likely feel soreness and fatigue during this stage.

- Resistance Stage: Your body adapts to the stress by getting stronger and more resistant. This is where you see improvements in your performance.

- Exhaustion Stage: If you continue to train without sufficient rest and recovery, your body will eventually become exhausted. This stage increases the risk of injuries, overtraining, and plateaus.

Incorporating it in your routine helps prevent reaching the exhaustion stage by allowing your body to recover. During a full deload period, you can reduce the load or intensity to 40-60% of your 1 rep max, giving your muscles and nervous system a chance to recuperate. This well-timed break can lead to improved performance and progression in your training.

Signs that You Need a Deload Week

Experiencing plateaus in your training progress is one indication that it might be beneficial for you. If you’re consistently working out but notice that your strength or performance has stopped improving, it could be a sign that your body needs a break to recover and rebuild.

Persistent fatigue or soreness beyond what is expected from your regular workouts is another sign that you should consider a deload week. When your body can’t recover completely between sessions, it may be time to reduce the intensity and volume of your training to allow for adequate recovery.

Feeling a decrease in motivation or enthusiasm for your workouts can also indicate the need for a deload week. Mental fatigue plays a significant role in your overall performance and should not be overlooked. A week of lighter training can help you regain your passion and focus for your training regimen.

Sleep disturbances, such as insomnia or unrestful sleep, may signal that your central nervous system is overtaxed. During a deload week, reduced training intensity can help your body and mind recover, leading to better sleep quality.

Lastly, if you’ve been consistently following a rigorous and challenging training plan for an extended period (about 4-6 weeks), it’s generally a good idea to schedule a deload week as a proactive measure to prevent overtraining and enhance overall recovery.

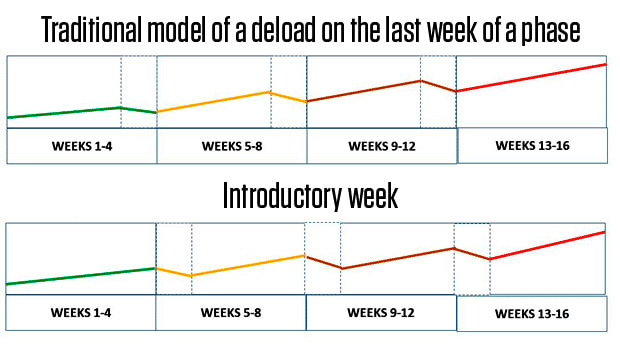

How to Program a Deload Week

Choose When to Deload

It should be incorporated strategically into your training cycle, usually every 4-6 weeks, depending on your training intensity and individual recovery needs. It is essential to listen to your body and pay attention to signs of fatigue, such as decreased performance, nagging injuries, or lack of motivation.

Choose What Kind of Deload to Take

Next, decide what type of deload to take. There are generally two options: reducing load/intensity or decreasing volume.

- Reducing Load/Intensity: This option involves maintaining your training volume but using 40-60% of your 1 rep max. By doing this, you allow your body to recover while still maintaining movement patterns and technique. This approach is suitable for individuals with higher training intensities who are more likely to experience fatigue from heavy loads.

- Decreasing Volume: This option involves cutting your training volume by 40-60% while maintaining your usual load/intensity. This approach is suitable for individuals more prone to fatigue from a high volume of training.

Remember to prioritize recovery. Ensure that you are getting adequate sleep, proper nutrition, and utilizing recovery techniques such as foam rolling and stretching.

Types of Deloads

Traditional Deload

The Traditional Deload is a popular and straightforward approach to deloading. In this method, you reduce your workout volume by 50% or more, and decrease the weight you lift for each exercise by roughly 10% for a week. This strategy effectively dissipates fatigue and enhances your recovery for the following week. It’s a solid option for those looking to maintain their current workout structure with a slight decrease in intensity and volume.

Autoregulated Deload

Autoregulated Deload is a more flexible and intuitive approach to deloading. Instead of adhering to the strict percentages used in the Traditional Deload, you listen to your body and adjust the intensity and volume based on how you feel. If you’re experiencing more fatigue than usual, you can reduce the workload accordingly, and vice versa. This method can be ideal for those who prefer a personalized approach to training and recovery.

Physique Deload

The Physique Deload is geared towards those looking to maintain or improve their muscular aesthetics. In this method, you continue to train at a high intensity (close to your 1 rep max), but you significantly reduce your workout volume2. This allows you to maintain muscle stimulation while giving your body ample recovery time. The Physique Deload is a great option for bodybuilders and fitness enthusiasts seeking to balance both performance and appearance goals.

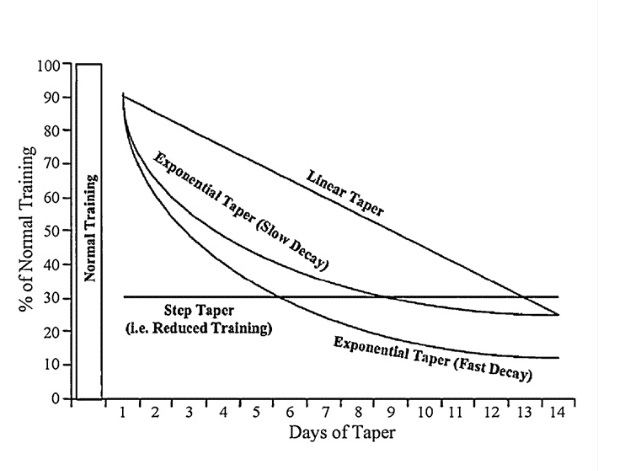

Progressive Taper Deload

The Progressive Taper Deload is a more gradual approach to deloading, focusing on slowly reducing your training volume and intensity over a period of several weeks3. This strategy is especially useful for those preparing for a competition or other event, as it allows for a smooth transition from high-intensity training to peak performance. By slowly tapering your workload, you can ensure that your body is adequately recovering without losing the desired adaptations from your training.

Benefits of Deloads

Bust Through Plateaus

We all encounter plateaus in our fitness journey, and one of the reasons can be overtraining. Deload weeks can help you bust through plateaus by giving your body a break from constant stress. This period of rest and active recovery provides an opportunity for your body to reset and be ready to tackle new challenges when you resume more intense workouts.

Boosts Muscle Hypertrophy

Although it might sound counterintuitive, taking a break from working out can actually aid in muscle growth. It allows your muscles and central nervous system the time they need to recover from previous weeks of intense training. This recovery process is essential for muscle hypertrophy, as the building of new muscle tissue relies on adequate rest and recovery.

Heart Health

During a deload week, you are giving your body a much-needed break. This allows your heart to recuperate from intense training sessions, leading to better heart health. Giving your cardiovascular system a chance to recover will serve you well in the long run, reducing the risk of heart-related issues.

Stronger Bones

In addition to improving heart health, deload weeks can also contribute to stronger bones. By temporarily reducing training stress, you’re allowing your body to recover and repair, which includes the strengthening of your skeletal system. This downtime will help support the development of stronger bones for improved overall health.

Psychological Benefits

Last but not least, deload weeks offer significant psychological benefits. Taking a week to focus on lighter workouts and active recovery can help reduce mental burnout and improve your overall mood. This intentional time for relaxation can lead to better mental health and a more sustainable approach to exercising, allowing you to feel refreshed and ready to tackle your workouts with renewed motivation and focus.

Who Should Schedule a Deload Week

Bodybuilders

During periods of intense training, your muscles and nervous system are constantly under stress. A deload week reduces the risk of overtraining, allowing your body to recover and adapt to the training stimulus. By incorporating a deload week into your routine every 4-8 weeks, you can keep progressing and avoid plateaus in your muscle and strength gains.

Strength Athletes

Strength athletes, such as powerlifters and weightlifters, should also embrace deload weeks. Heavy lifting and strength training puts immense strain on your joints, connective tissues, and central nervous system. By reducing your training intensity for a week, you give your body a chance to recuperate and come back stronger.

CrossFitters

The high-intensity nature of CrossFit workouts and hard training demands a lot from your body, and therefore requires sufficient recovery time. A well-timed deload week can enhance your performance in future workouts, reducing the risk of burnout, and helping you maintain a consistent training schedule while promoting overall health.

Recreational Athletes

Finally, even if you are a recreational athlete, scheduling a deload week is important, as it ensures that you maintain a healthy balance between exercise and recovery. By actively dedicating a week to lighter training or activities, you avoid the pitfalls of overtraining and reduce the chances of injuries that could hinder your long-term progress.

Sample Deload Week

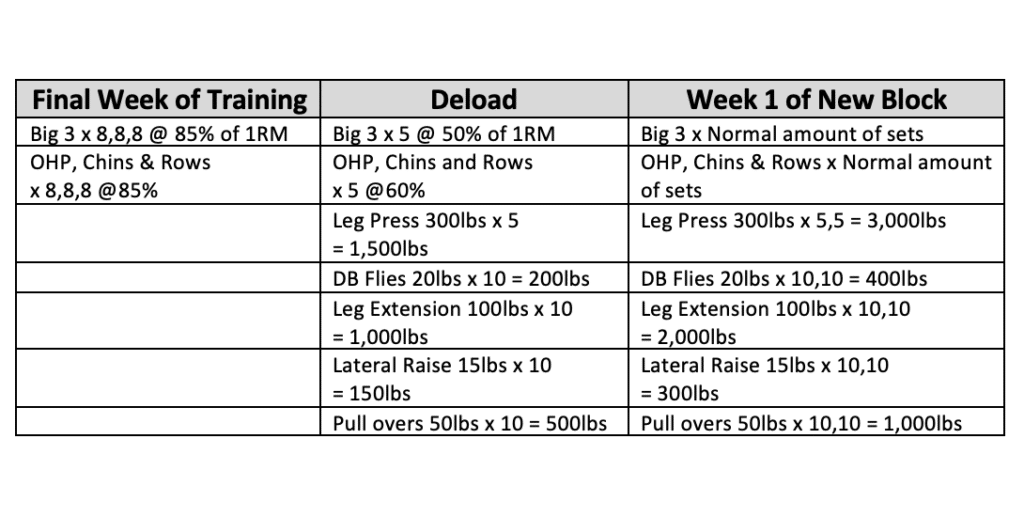

The main focus is to give your body the rest it needs to recover from intense training. This helps you avoid overtraining and prepares you for heavier workouts in the coming weeks. Here’s a simple sample deload week to guide you through the process.

Day 1: Upper Body

On the first day, concentrate on upper body exercises. Reduce the weight and volume of your regular workout, and focus on maintaining proper form.

- Bench Press: 3 sets of 8 reps with 50-60% of your regular weight

- Pull-ups: 3 sets of 5 reps (use a band for assistance if needed)

- Overhead Press: 3 sets of 8 reps with 50-60% of your regular weight

- Face Pulls: 3 sets of 12 reps with light resistance

Day 2: Lower Body

The second day is dedicated to lower body exercises. Again, reduce the weight and volume compared to your regular workout.

- Squats: 3 sets of 8 reps with 50-60% of your regular weight

- Deadlifts: 3 sets of 5 reps with 50-60% of your regular weight

- Leg Press: 3 sets of 10 reps with 50-60% of your regular weight

- Leg Curls: 3 sets of 12 reps with a lighter resistance

Day 3: Active Rest

Instead of a regular workout, take part in a light activity such as walking, cycling, or swimming for 30-45 minutes to help promote blood flow and recovery.

Day 4: Full Body

On the fourth day, perform full-body exercises with a focus on maintaining proper form and reduced weight.

- Push-ups: 3 sets of 10 reps

- Bodyweight Row: 3 sets of 10 reps

- Bodyweight Lunges: 3 sets of 12 reps per leg

- Plank: 3 sets of 30-second holds

Day 5: Mobility and Stretching

Dedicate this day to improving your mobility and flexibility. Spend 20-30 minutes going through a series of stretches and mobility exercises, targeting sore joints and muscles that feel tight or need extra attention.

Day 6 and 7: Rest

For the last two days of your deload week, take complete rest. This will give your body a chance to fully recover and prepare for the upcoming three weeks of intense training.

Remember, this is just a sample deload week. You can customize it according to your needs and preferences. The key is to reduce the intensity and volume of your workouts, allowing your body to recover and come back stronger.

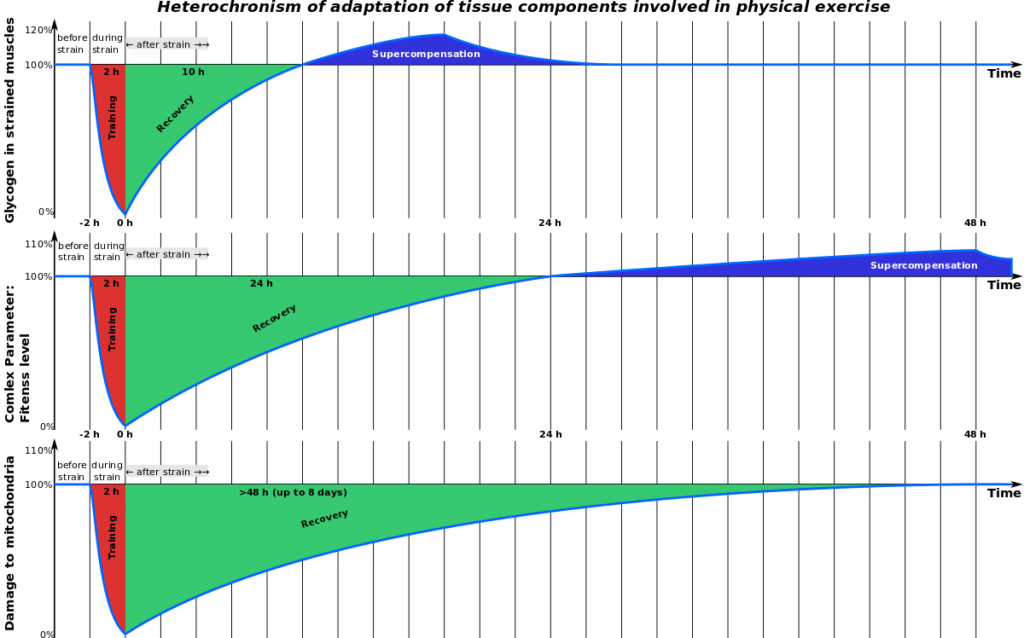

The Science Behind Deloading

The concept of a deload week is based on the principle of supercompensation. In simple terms, supercompensation occurs when your body recovers and adapts to the stress you’ve placed on it, leaving it stronger and more resilient than before. Here’s a breakdown of how this theory applies to deload weeks:

- Stress: You push your body during intense training sessions, creating a stress on your muscles, joints, and nervous system.

- Recovery: After each workout, your body begins the process of recovery, repairing damaged tissues and replenishing energy stores.

- Adaptation: As your body repairs itself, it also adapts to better handle the stress you imposed on it, resulting in increased strength, endurance, or muscle mass.

What Should You Do After Your Deload?

It’s important to gradually return to your regular training routine. This will help you benefit from the recovery period, allowing you to make progress and continue gaining strength. Here are the key steps to follow after a deload week:

Firstly, begin by evaluating your performance during the week and noting any improvements or areas that still require attention. It’s important to remember that the purpose is to enable your body to fully recover so that you can come back stronger.

Next, gradually increase the intensity and volume of your workouts. Avoid jumping straight back into your previous workout routine, as this may cause undue stress on your body and potentially lead to injuries. Instead, start by incorporating around 70% to 80% of your pre-deload training volume, and slowly work your way back up over the following weeks. This will ensure a safer transition and allow you to monitor any lingering fatigue.

It’s also essential to listen to your body and continue practicing good recovery habits. This includes getting enough sleep, maintaining proper nutrition, and managing stress levels. By prioritizing your overall well-being, you can optimize your training and make the most out of the deload week’s benefits.

Finally, use the insights gained during your deload week to refine your training program. Make any necessary adjustments to your routine, such as modifying exercise selection, rep schemes, or set structures. This will help you avoid plateaus and continue making progress towards your fitness goals.

Frequently Asked Questions

How often should a deload week be implemented?

Generally, it is recommended to schedule a deload week every 4-6 weeks for optimal recovery and performance. However, it’s crucial to listen to your body and adjust the frequency according to your progress and recovery levels.

What are the benefits of a deload week in powerlifting?

Deload weeks in powerlifting are essential for allowing your body to recover from the stress of heavy lifting. They help prevent overtraining, reduce the risk of injury, and promote muscular and nervous system recovery. By incorporating them into your program, you can enhance your overall performance and progress in powerlifting.

What percentage of weight should be used during a deload week?

During a deload week, it is advised to reduce the weight you’re lifting to about 40-60% of your 1 rep max. This means you might use around half of the weight you normally lift during your sets. This reduction allows your body to recover while still maintaining some training stimulus.

How does a deload week affect bodybuilding training?

It can enhance your performance and minimize the risk of injury by giving your muscles a chance to recover. The benefits of a deload week are not solely for powerlifters; bodybuilders can also use this period to improve muscle growth, as recovery is a critical part of muscle hypertrophy.

What is the role of cardio during a deload week?

Cardio can be incorporated during a deload week, but it’s important to keep the intensity low. Light cardio, such as walking or swimming, can help maintain cardiovascular fitness without adding extra stress to your muscles. It’s essential to avoid high-intensity cardio workouts during the week to ensure your body can fully recover.

When is the best time to schedule a deload week in a training program?

The best time to schedule it in a training program depends on your individual progress and recovery needs. As a general guideline, you should consider scheduling one after a period of high-intensity training or once you start experiencing signs of overtraining like lethargy, loss of appetite, or inability to concentrate.