This essential back squat guide is designed to elevate your technique to professional levels. From the foundational setup to the detailed nuances of each movement, we explore the scientific and practical elements of performing a back squat with precision and power.

Ideal for both beginners and experienced athletes, this article will transform your understanding of barbell placement, hand positioning, and body tension.

Read on to not only refine your squat form but also to significantly reduce the risk of injury, ensuring a more effective and safe training experience.

Related: See the before and after squat examples and get inspired!

Jump to:

Proper Back Squat Technique and Form

Starting Position and Setup

Mastering the back squat begins with a solid starting position. This foundational setup is crucial for a successful lift and minimizing injury risk.

Barbell Placement on the Upper Back

The barbell’s position can make or break the squat. It should rest comfortably on the trapezius muscles, just below the neck. This high-bar placement ensures a more upright torso, essential for proper squat form. Athletes should feel the weight evenly distributed across their shoulders, creating a stable base for the lift.

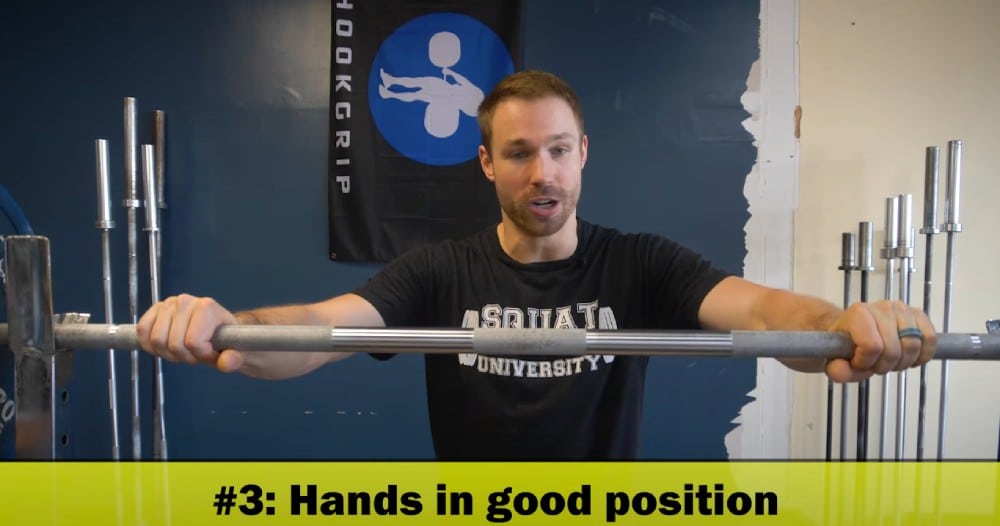

Hand Positioning

Hand placement on the barbell is not merely a matter of comfort; it’s about control. Hands should be placed just outside the shoulders, gripping the bar firmly. This positioning not only stabilizes the bar but also helps in creating a tight upper back, a critical aspect for maintaining proper posture throughout the squat.

Creating Tension in the Upper and Lower Body

Tension is the secret ingredient for a powerful squat. Before descending, athletes should take a deep breath (Studies advise inhaling about 80% of their maximal capacity) and brace their core, creating intra-abdominal pressure. This act of bracing safeguards the spine and provides a strong foundation.

Simultaneously, feet should be shoulder-width apart, with toes slightly pointed outwards. Driving the knees outwards while squatting down ensures stability and engages the correct muscle groups effectively.

Feeling geeky? Here are super detailed pointers given by scientists on how each body part should be positioned for an Optimal squat:

- The athlete’s head should maintain a neutral to slightly extended position in relation to the spine.

- The neck should align with the plane of the torso.

- The gaze should focus straight ahead or slightly upward, especially during the ascent phase of the squat. This helps guide the movement, leading with the head and chest, and prevents excessive forward trunk flexion.

- The thoracic spine should be slightly extended and held rigid.

- The chest is directed outward and upwards, contributing to a more vertical torso angle.

- This position should be consistent throughout the entire squat movement.

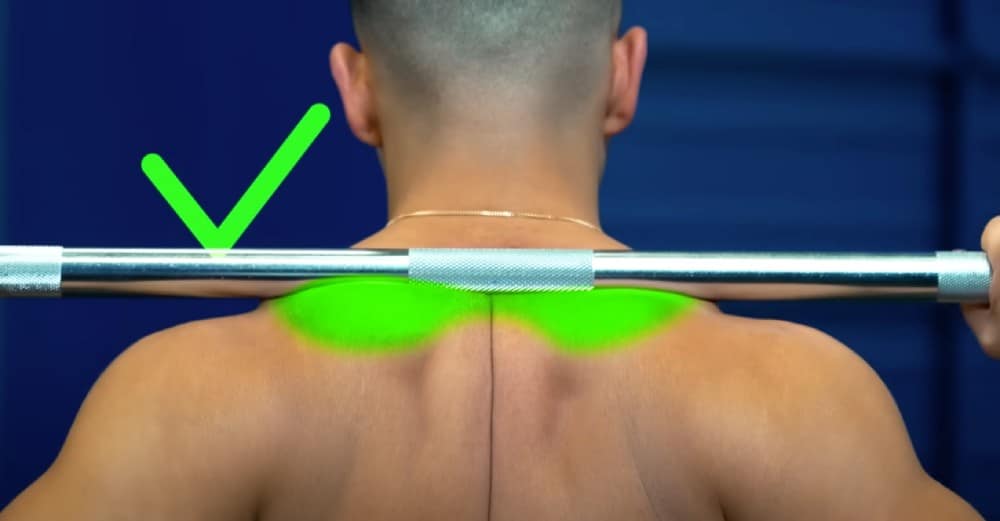

- The scapulae (shoulder blades) should be retracted (pulled back) and depressed (lowered), while the shoulders are slightly rolled back.

- The forearms should align parallel to the spine, ensuring the shoulders are retracted and not rolled forward.

- This position engages major supporting back muscles like the latissimus dorsi, erector spinae, trapezius, and rhomboids, maximizing spinal stability.

- A tight upper back with retracted scapulae also provides a secure position for the dowel during back squats.

- The lumbar vertebrae should maintain a neutral alignment throughout the squat, with a slight lordotic curve in the lumbar region.

- The abdomen should be held upward and rigid for stability.

- The trunk should remain as upright as possible to minimize lumbar shear forces associated with forward lean.

- Stability of the trunk is key, without wavering or displacement.

- A guideline for proper trunk posture is to keep the trunk parallel to the tibias when viewed from the lateral perspective.

- The athlete should maintain square, stable hips with minimal side-to-side movement.

- Hip position should be symmetrical, with the line of the hips parallel to the ground from the frontal perspective.

- Pelvis should be in a neutral tilt, especially during the descent phase of the squat.

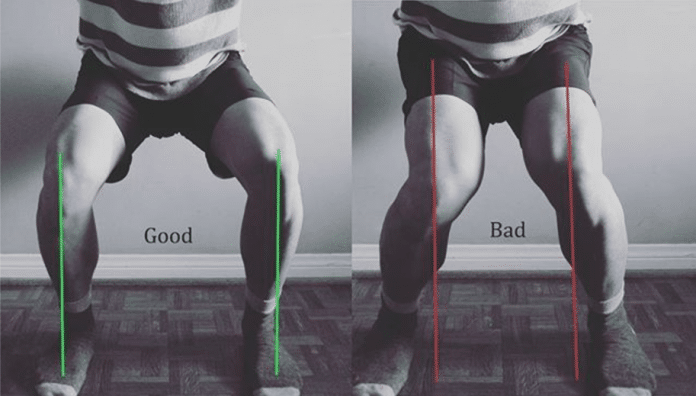

- Knees should track over the toes throughout the squat, maintaining a neutral frontal plane position.

- There should be no medial or lateral knee displacement.

- The lateral aspect of the knee should not cross the medial malleolus, and the medial aspect should not cross the lateral malleolus.

- Feet should be stable and firmly planted on the ground throughout the squat.

- Weight distribution should shift from mid-foot to heel and lateral foot during descent.

- Emphasize body weight through the heel and lateral foot while keeping toes on the ground for balance.

- This foot positioning aids in hip motion strategies and gluteal muscle recruitment.

Execution of the Squat: Mastering the Movement

Here’s me (Julien Raby) getting 335 lbs, with possibly the worst technique ever. Here’s what NOT to do…

Hip and Knee Alignment

Proper alignment of hips and knees is crucial for an effective back squat. As you descend, hips should move back and down, while knees track in line with the toes. This alignment not only engages the right muscle groups but also protects the knees from undue stress. Remember, knees pushing slightly past the toes is acceptable, provided they remain in line with them.

Depth of the Squat

Achieving the right depth in a squat is a balancing act. The goal is to lower the hips below parallel to the knees, ensuring a full range of motion. This depth maximizes muscle engagement and strength development. However, depth should not compromise form. If mobility issues arise, work on them progressively to achieve the ideal depth.

Maintaining Balance and Stability

Balance and stability are the unsung heroes of a successful squat. Weight should be evenly distributed across the feet, with a focus on driving up through the heels. This ensures a stable base and prevents tipping forward or backward. Engaging the core throughout the movement is key to maintaining balance and protecting the spine.

Breathing Techniques

Breath control plays a pivotal role in the execution of a back squat. Inhale deeply before descending, and hold this breath to create intra-abdominal pressure, which stabilizes the spine. Exhale forcefully on the way up. This technique, known as the Valsalva maneuver, is a game-changer for maintaining stability and power during the lift.

Tips and Cues to Improve Your Back Squat

Proper Equipment Use

Utilizing proper training equipment like belts or knee sleeves can not only keep everything tight and safe but also help lift more weight. This can be a significant factor in enhancing squat performance.

Breathing Technique

Correct breathing is crucial throughout the squat movement. A deep inhale with the diaphragm at the start helps gather tightness in the midline, controlling the spine and core during the lift.

Holding your breath on the way down and exhaling slowly on the way up maintains midline tension, which is vital for protection and performance.

Foot Positioning and External Rotation

Slight toe out and symmetrical foot positioning are recommended. Creating external rotation torque by driving knees out slightly while keeping feet planted and engaged activates the hips and lateral glutes, providing a stable base for the squat.

Barbell Handling and Unracking

The bar should be stabilized between the palms and upper back without actively gripping it like in a bench press. Push hips forward to unrack the bar, avoiding quad fatigue before the lift. Take minimal steps backward to establish foot position.

Bracing Phase

Ensure even pressure on the ground with the heel and big toe, and weight centered on the middle of the foot. Avoid keeping weight solely on the heels as it can throw off balance and cause early hip rise.

Depth and Ankle Mobility

Aim for a depth where hips descend lower than knees. If limited ankle mobility or a weak core and glutes hinder depth, try elevating heels on weight plates or using more stable exercises like Smith machine squats before progressing.

Muscle Engagement

Quad engagement increases with deeper squats. Glutes control the descent rate and help extend hips to return to standing. The spinal erectors maintain an upright torso, especially in high-bar back squats.

Knees Over Toes Myth

Letting your knees come forward past the toes is actually not harmful and trying to keep them behind can be detrimental to the lower back.

Balance and Force Production

Ensure your upper body is in balance during the squat. An off-balance athlete cannot produce efficient force and power. The barbell should track directly over the middle of your foot.

External Rotation Torque

Create external rotation torque by driving knees out slightly while keeping feet grounded. This activates the lateral glutes, enhancing stability and power in the squat.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Back Squatting

Half-Squatting

A frequent error in back squatting is half-squatting, where one fails to reach the full depth. This mistake limits the exercise’s effectiveness, reducing engagement in key muscle groups. Aim for hips below knee level to ensure a full range of motion, maximizing strength gains and flexibility.

Knee Valgus Correction

A common error is knee valgus, where knees cave in during the squat. This often stems from inadequate hip external rotation. To correct this, ensure feet are adequately flared out and actively drive knees out in the direction of your toes, but not excessively beyond them. Using a mini band or hip circle around your knees can cue this and strengthen hip abductors. Wearing a heeled squat shoe may also help.

Hips Shooting Up

Maintain a consistent torso angle throughout the squat. If your back is stronger than your legs or you stand up too quickly, you risk keeling over as your pelvis shoots out behind you.

Overambitious Weight Selection

Lifting weights that are too heavy is a common pitfall. This not only hampers form but also increases injury risk. Start with a manageable, light weight first, focusing on technique. Gradual increments are the key to sustainable progress and strength development.

Rest Periods

Insufficient rest between sets can lead to fatigue and poor form. Adequate rest is crucial for muscle recovery and performance. Typically, resting for 2-3 minutes between sets allows for sufficient recovery, ensuring each set is performed with optimal strength and form.

Technique Neglect

Neglecting proper technique is perhaps the most critical mistake. Proper form ensures safety and effectiveness. Pay attention to foot placement, knee alignment, and maintaining a straight back. Regularly revisiting and refining technique, even for experienced lifters, is essential for continued improvement and injury prevention.

Safety and Injury Prevention in Back Squatting

Gradual Progression and Proper Warm-Up

The journey to mastering the back squat begins with gradual progression and a proper warm-up. It’s essential to build strength and flexibility steadily, avoiding the temptation to rush into heavy weights. A comprehensive warm-up routine, focusing on mobility and activating key muscle groups, sets the stage for a safe and effective workout. This approach not only prepares the body for the demands of squatting but also enhances overall performance.

Common Injuries

Improper technique in back squatting can lead to several injuries, with the lower back, knees, and hips being the most vulnerable. Strains and sprains are common when lifters compromise form, especially under heavy loads. Understanding these risks underscores the importance of correct technique and body alignment during every phase of the squat.

Injury Prevention and Recovery

Preventing injuries in back squatting involves a multifaceted approach. Firstly, always prioritize form over weight. Ensure that movements are controlled and precise. Incorporating flexibility and stability exercises into your routine can greatly reduce injury risk. Additionally, listening to your body and allowing adequate recovery time is crucial. If an injury does occur, seek professional advice and focus on rehabilitation exercises to facilitate a safe return to squatting. Remember, the path to strength is a marathon, not a sprint.

Variations and Modifications of the Squat

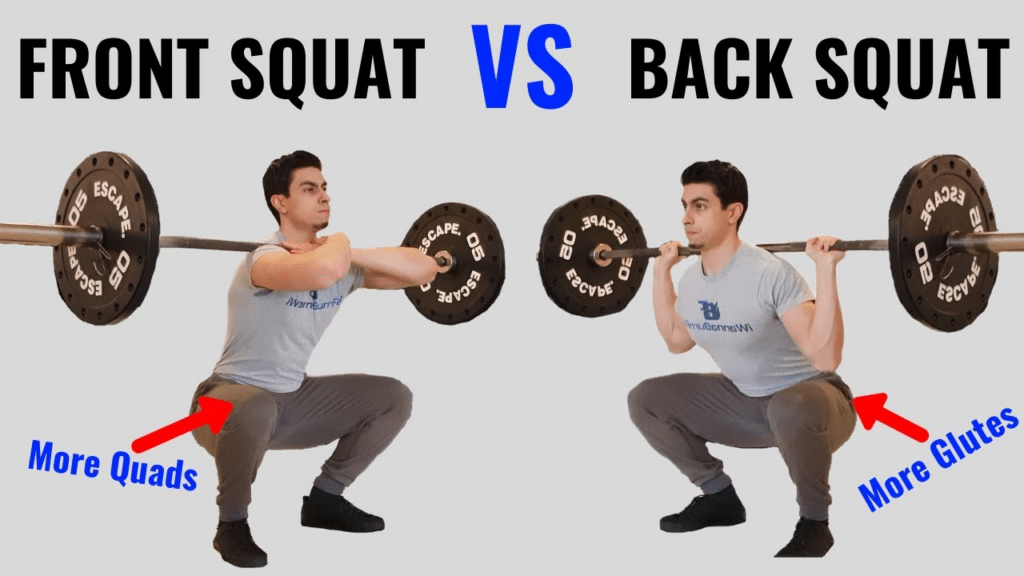

Front Squat vs. Back Squat

In the realm of squats, the front and back squat variations can stand as two pillars, each with unique benefits. The front squat, characterized by the barbell resting on the shoulders, emphasizes the quadriceps and upper back, promoting an upright torso. Contrastingly, the back squat, with the barbell positioned across the upper back, engages the posterior chain more significantly, including the glutes and hamstrings. Both variations are invaluable, yet they cater to different strength and mobility requirements.

Goblet Squat and Beyond

Diversity in squatting extends beyond the classic front and back variations. The goblet squat, involving a kettlebell or dumbbell held at chest level, is a fantastic option for beginners, enhancing squat depth and form. Other variations like the sumo squat, with a wider stance, target the inner thighs and glutes differently. Each variation offers a unique challenge and benefit, making squats a versatile tool in any fitness regimen.

Modifications for All

Squats are adaptable, catering to individuals with specific needs or limitations. Modifications can range from altering the squat depth to using assistive devices like squat racks or resistance bands. For those with knee issues, box squats provide a safer squat alternative, allowing control over the squat depth. Tailoring the squat to individual capabilities ensures that everyone can safely enjoy the benefits of this foundational exercise.

Incorporating Back Squat into Training Programs

Frequency and Volume

Incorporating back squats into training regimens requires a delicate balance of frequency and volume. For beginners, squatting twice a week can be a solid start, allowing muscles to adapt while minimizing the risk of overtraining. As proficiency grows, increasing frequency to three times weekly can accelerate strength gains. Volume, measured in sets and reps, should align with individual goals. For strength, fewer reps with heavier weights are key, while endurance calls for higher reps at lower weights.

Progressive Overload and Periodization

Progressive overload, the gradual increase of stress placed on the body during exercise, is crucial for continual strength and muscle development. This can be achieved by increasing the weight, reps, or sets over time. Periodization, involving varying training intensity and volume across different phases, prevents plateaus and overtraining. A well-structured periodization plan can include phases of hypertrophy, strength, and power, each tailored to enhance overall performance in back squats.

Synergy with Other Exercises

Back squats don’t exist in isolation. Integrating them with complementary exercises enhances overall athletic performance. For instance, pairing squats with deadlifts can improve posterior chain strength, while combining them with plyometric exercises like box jumps can boost explosive power. Additionally, incorporating mobility work and core strengthening exercises ensures a well-rounded approach, reducing injury risk and improving squatting efficiency. This holistic integration ensures that back squats contribute significantly to a comprehensive fitness journey.

Benefits of Back Squat

Strength and Muscle Development

Back squats are renowned for their unparalleled ability to develop strength and muscle. This compound exercise targets not just the legs but also engages the core, back, and shoulders, offering a full-body workout. Regular squatting leads to significant gains in muscle mass, particularly in the lower body, laying a solid foundation for overall fitness.

Athletic Performance

Athletes across various disciplines incorporate back squats into their training for a reason. This exercise enhances explosive power, critical for sprinting, jumping, and swift directional changes. Improved athletic performance is a direct outcome of the dynamic strength and endurance built through consistent squatting.

Bone Density

An often-overlooked benefit of back squats is their impact on bone density. Weight-bearing exercises like squats stimulate bone growth, crucial for long-term health and injury prevention. This aspect is especially beneficial for aging athletes, helping them maintain a robust skeletal structure.

Functional Movement

Back squats don’t just build muscles; they improve functional movement. This exercise mimics everyday actions like lifting and bending, making routine tasks easier and reducing the risk of injury. Enhanced functional movement leads to a better quality of life, both inside and outside the gym.